HYGIENE. A thing that might sound simple and obvious to many. But the truth flashes with the yearly death of 2.4 million globally due to lack of hygiene, sanitation, and water. The practice of open defecation (OD) is considered one of the major causes of the persistent worldwide burden of diarrhoea and enteric parasite infection among children under the age of five, which lead to preventable deaths. The attempt to reduce OD requires access to and use of improved sanitation facilities.

The challenges of ending open defecation in India

Most developing countries, consider open defecation is the 'way of life' which in reality is the “riskiest sanitation practice of all” according to World Health Organization. Nearly 60 per cent of the people in the world who defecate in the open belong to India; popular reasons being lack of interest, money and space. " Open defecation (OD), an age-old practice in India, impacts the health of individuals as well as their communities. To tackle the problem and accelerate the efforts for achieving universal sanitation coverage, the Government of India launched the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) in 2014, aimed at making the country open-defecation free (ODF) by giving more attention to community-based approaches.

However, while such approaches have helped solve the sanitation riddle in many countries, curbing OD in India is much more complicated: the root of the problem is a combination of lack of sanitation infrastructure and deep-seated habits. According to the NFHS-5, 19.4 per cent of the country does not have access to a toilet — of which 25.9 per cent is in the rural areas where people are still “comfortable” in going to open grounds. In Delhi slums for instance, where the reliance on community toilet centres is high, it was found that the community members were uncomfortable using these community toilets, complaining of feeling of suffocation.

Taking the bottom-up approach

Sanitation policies have for long taken the top-down approach, focusing on financial assistance for latrine construction. While this is necessary, considering the social determinants at play, the emphasis must be on changing collective behaviour through participatory methods. When SBM moved towards bottom-up approach to behaviour change through Information Education and Communication (IEC) and Inter-personal Communication (IPC) strategies to “trigger” the communities, the nation saw over six-lakh Swachhagrahis battling the issue of hygiene. Panchayat members, ASHA and Anganwadi workers, women, children, youth workers, school teachers, senior citizens, and the differently abled took ownership, and led the Swachhata brigade in their communities.

The journey of Kanhaiya

Following this blueprint for large scale participatory development programs, a young changemaker Kanhaiya, a batch 16 Gandhi Fellow of Bhagalpur, Bihar set on his journey of a change maker. While completing his CI journey, he experienced how age-old habits veil the urgency of addressing social problems in India.

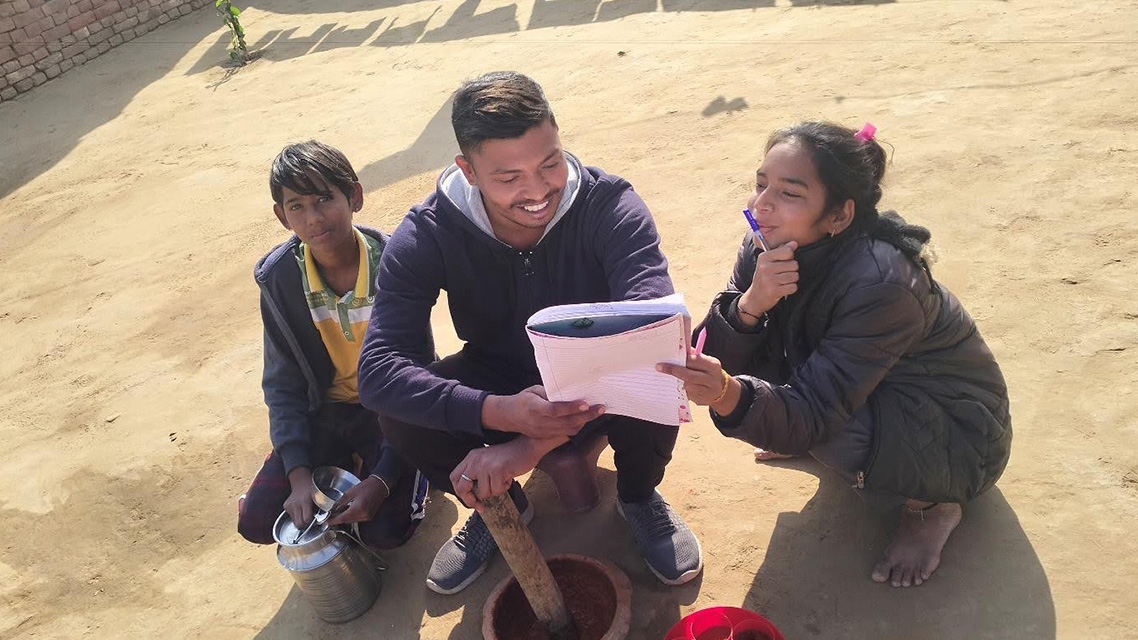

The story begins with the most meaningful 30 days of his young life, the Community Immersion journey of Kanhaiya in Santor village, a rural community of Buhana Block in Jhunjhunu District of Rajasthan. It started as a part of Kanhaiya’s fellowship curriculum and ended up with him being an inspiration for the entire village. He was graciously invited to share the home and traditions of a daily-wage labour family of 5 members. It was a happy family of Amarjeet Kayat and his wife Manisha, their two daughters Arzoo & Priti, and son Amit. The best part of the family was they were always up for a conversation yet giving space to each other.

Kanhaiya soon blended with their daily lives. From participating in traditional rituals to immersing myself in the local culture, he found himself embracing every moment with an open heart. The closeness to the community exposed him to cherished friendships and some harsh realities. From domestic violence to a lack of awareness about basic rights and needs, to the absence of public transport connecting the community to nearby cities, the list was daunting. Unable to decide where to start, he decided to take the smallest step first. Every change starts as home- remembering this Kanhaiya started thinking about the home he was living in. Santor, like many rural areas, struggled with limited sanitation facilities. Only a handful of houses had toilets, and the rest of the community relied on an open area for their daily constitutional. This not only posed health risks but also affected the overall well-being of the residents. Undeterred by the initial struggles and challenges of adapting to the community, Kanhaiya was determined to make a positive impact.

During communal dinners, Kanhaiya began engaging in conversations about the importance of sanitation. The community faced a dual challenge: water scarcity and financial constraints. Kanhaiya quickly became aware of the challenges the community faced, particularly the widespread practice of open defecation. Though he did not have any prior knowledge to bring to this task, Kanhaiya was undaunted, to build a toilet for his host’s home. Counting on resources, Kanhaiya remembered the first day of his community immersion when he joined Amit and his uncle to collect wood from the nearby area for firewood. That was the first time, Kanhaiya used an axe. He estimated there would be more tools that can be used to build the toilet. Drawing from his online experiences, he gathered insights and techniques to modify existing tools for the task.

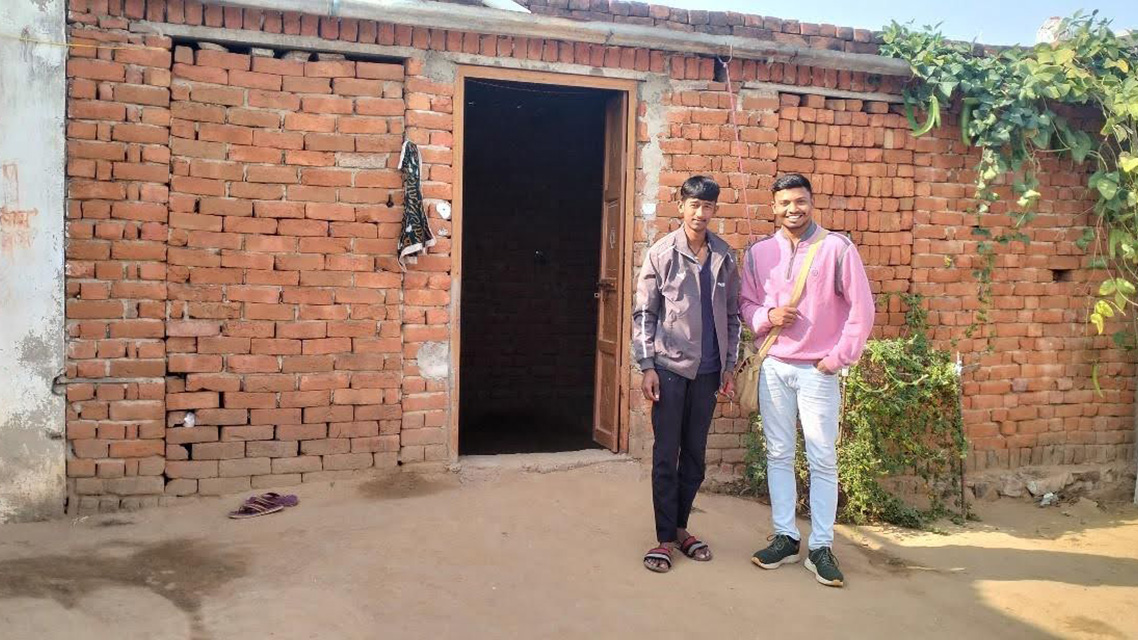

Accordingly, he initiated a budgeting exercise, utilizing available raw materials within the community. Still the major setback on finance came when they estimated the expense of digging up a well. Usually, a professional charge 7 to 8 thousand which Kanhaiya thought can be saved with physical effort. He himself decided to give it a try along with Amit who was familiar with the process.

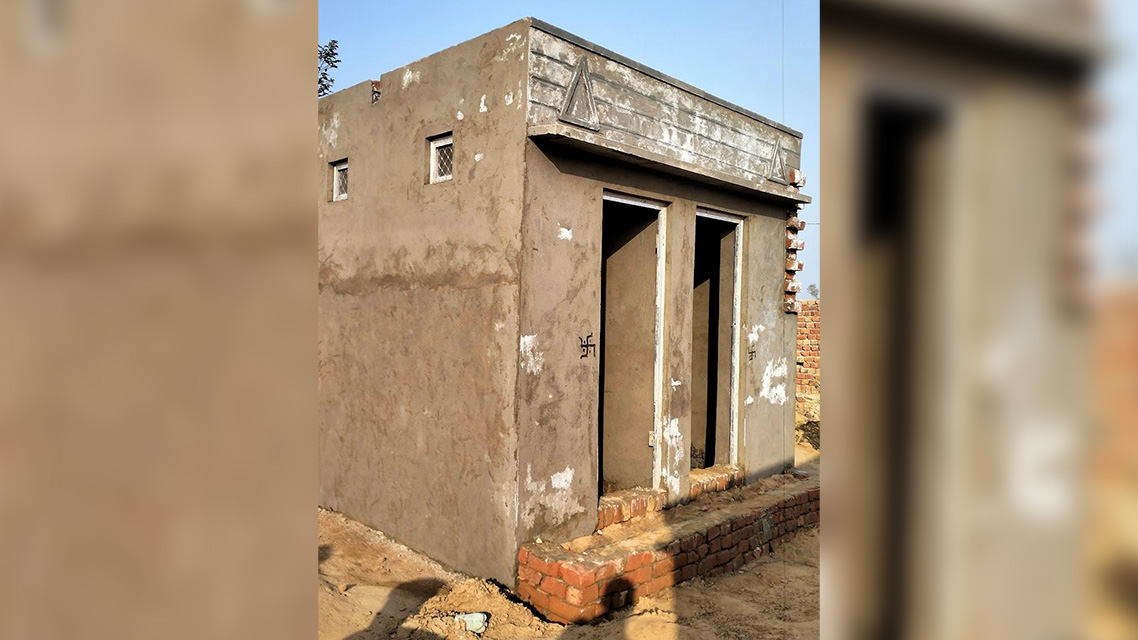

It was not something he did earlier, so he started his research and they both started working within few days. The first five feet was fuelled by enthusiasm and passion. But as he started digging deeper, he started realising the struggle. After several feet the ground became rocky and was very hard to dig with the existing tools. They were able to dig only 2 ft in the whole day. failed in their attempts a few times bringing them to the verge of quitting. The villagers started mocking them and calling their efforts futile. Despite the difficulties and lack of encouragement, Kanhaiya was determined to complete what he had started. At the end of 7 days, the well finally got completed. Soon after, the construction of the toilet room was completed and Kanhaiya’s new family have their own private toilet.

To watch Kanhaiya's transformative journey firsthand

Overcoming challenges and Empowering self and community

The impact of Kanhaiya's efforts reached beyond the well they had dug. Inspired by his dedication and commitment, other families in the community realised that they can also build a toilet for their homes. The awareness that began as part of Kanhaiya's fellowship journey now evolved into a community-wide movement, transforming not just sanitation practices but also fostering a sense of unity and shared responsibility among the village community.

Through his actions, he showcased a tangible solution to a pressing issue and ignited a spirit of empowerment and community well-being. The village of Santor witnessed a transformation, thanks to the inspiring journey of the young man who believed in the power of change from within.

To view heartfelt messages from community members expressing gratitude to Kanhaiya for his transformative efforts

Acknowledgement

I extend my heartfelt gratitude to all those who contributed to the creation of this case study. First and foremost, I thank Kanhaiya and his community for generously sharing their stories and experiences. Without their openness and willingness to engage in dialogue, this narrative would not have been possible. I am indebted to the organizations and institutions whose research and insights form the foundation of this case study. I would also like to express my gratitude to Geeta for providing the required direction to this case study. Her guidance and expertise have been invaluable in shaping the narrative and ensuring its coherence and relevance.

Conclusion

From battling open defecation to fostering sanitation awareness and bringing about community ownership, Kanhaiya's brought a sustainable change. His impact resonates as a transformative journey that strives to builds a cleaner and healthier Bharat. Kanhaiya's impactful 30-day journey in Santor vividly illustrates his vision of Building Bharat as a Changemaker. His steadfast commitment not only led to construction of an essential facility but also illuminated the path for community-wide transformation.

Sources

https://india.un.org/en/171844-health-water-and-sanitation

https://eastasiaforum.org/2022/07/02/solving-indias-sanitation-scourge/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5427859/

TAGS

SHARE